Browse Topics

Adoption

Gratitude

A second chance at work, a shared meal in the classroom, a helpful stranger at a rest stop

November 2023All In The Family

Faith Friedlander On Adoption And Parenthood

Not every adopted adult needs the same thing, but I do think most adoptees, at some point in their lives, will want to look into their past. And someone in their birth family might come searching for them. With the Internet and readily available DNA tests, it’s not so easy to hide anymore.

September 2022Essays For My Daughter

I leave with my sunglasses on, waving my hand. Sometimes you call my name, your voice a taut string, and I think Michael might snap in half. But it’s strong — a tether.

May 2022Bella

How do you know when it’s time to take your autistic, bipolar twelve-year-old daughter to the psych ward? (They call them “behavioral units” now.) Is it when you find yourself sitting on her back and holding her arms to the ground while your wife lies on her legs? When she head-butts you the first time? The fifth? When she spits in your face?

March 2017And Now, Our Son On His Violin

My mother has been gone for some years, and though I do miss her and think of her with great fondness, part of me still has trouble forgiving how she would parade me out as a child to play my violin for unfortunate guests.

February 2013Girl, Ruined

One December morning in 1967, in the early hours before a dull winter sunrise, I labored alone on the fourth floor of Immanuel Hospital in Omaha, Nebraska. I had expected labor to be work, more or less like it sounded: teeth-gritting effort, sweating, and grunting. Instead furious stallions stampeded across my eighteen-year-old belly, and no amount of shameless screaming in the direction of the fluorescent-lit hallway could quiet them.

November 2010The Classified Ad

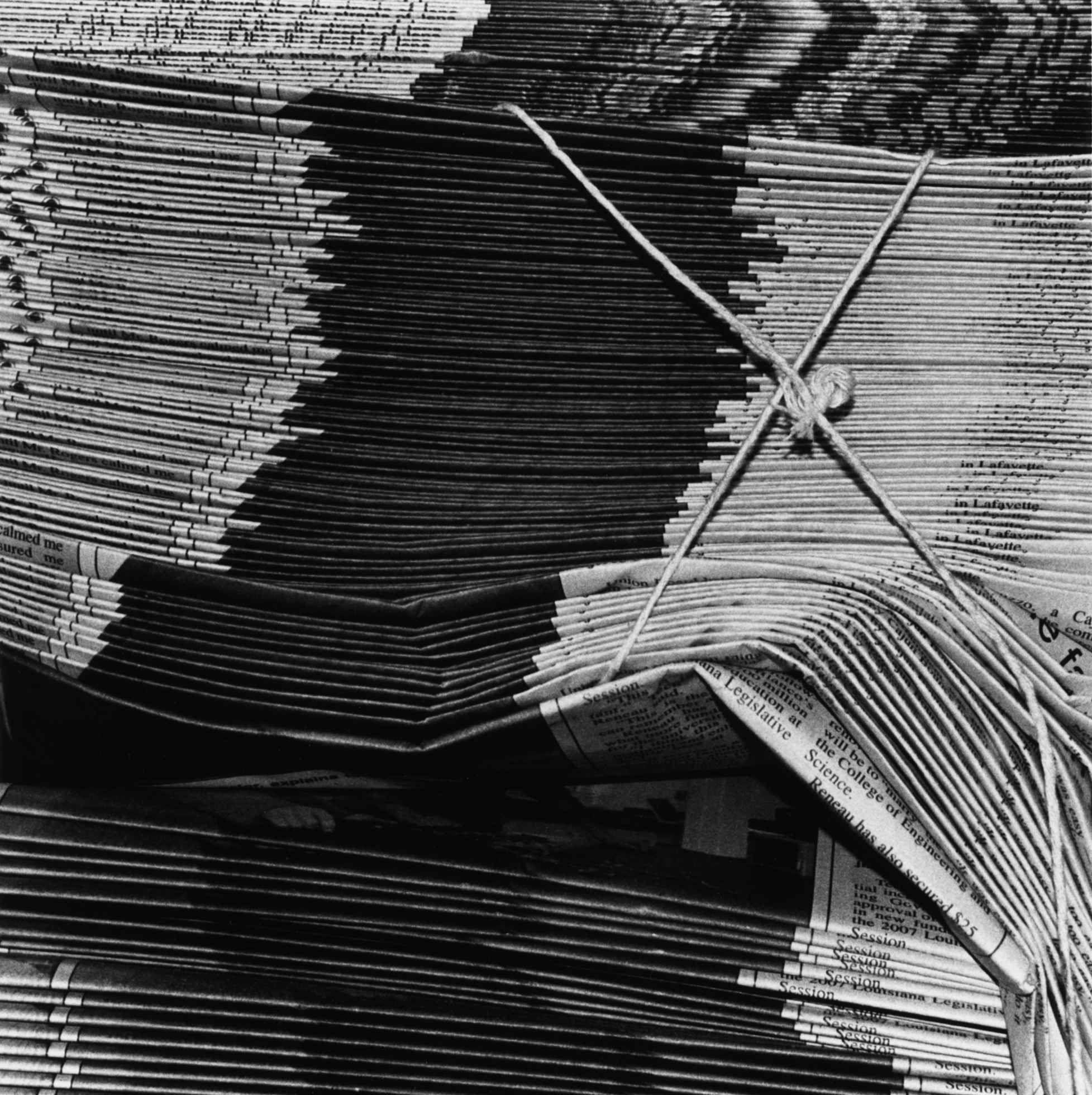

The Sumner Press, the weekly paper from my hometown in southeastern Illinois, continues to arrive in my mailbox in Ohio even though I’m not a subscriber. A few years ago, when my wife and I were the grand marshals for the Sumner fall-festival parade, the publisher gave us a complimentary one-year subscription. The subscription has run out, but the paper keeps coming, as if a higher power has decided I need it in my life.

September 2009Especially Roosevelt

Haiden’s morning sickness was bad, and she told me to get the boy out of the house, take him anywhere. She stood in the doorway of our downstairs bathroom, just off the kitchen, her frizzy black hair bound into a ponytail that pointed toward the ceiling like a squat exclamation point. “Please,” she said.

April 2008Me Me Me

When my sister Fawn told me she’d decided to adopt a little girl, I was skeptical. The girl’s name was Sam, and she lived in a group home run by — according to Fawn — gang members, illiterates, and pervs. Fawn had a master’s in social work and had been working with lost youth for years.

November 2007A Night Of Falling Alone

“Son, will you come downstairs, please.” He has pulled a chair up to the couch in the living room. We never use this room. The Christmas tree is placed in here each year. I would read in here as a child. That’s it. I sit on the couch and sink down. He sits straight up in the chair, his graying black hair combed back. His eyes soften. Like the sails on a boat, they offer a telltale sign of which way the wind is blowing and how strong. This afternoon, in the fading light of day, they tell me he is tired.

December 2003